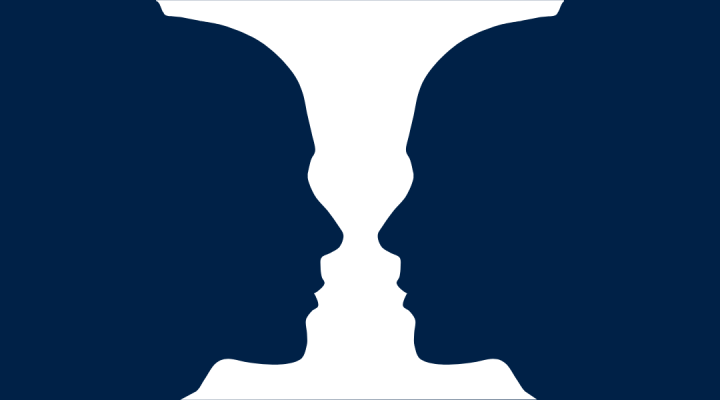

With the rise of the brand and the mission statement, organisational identity and purpose has become singular. But is such clarity always a good thing?

Cogency and clarity of purpose have been cemented into management behaviour with the growth and investment in the ‘brand. However, a quantum shift in societal norms is throwing up challenges to the notion of a singular business purpose. Several solutions exist to contend with the contradictory requirements society may thrust upon business but key amongst these is a willingness to embrace organisational ambiguity and to offer different values to different customer cohorts. Our recent research at Oxford University’s Saïd Business School provides a case study demonstrating how ambiguity can be more beneficial for business than organisational clarity

Elevate your thinking

Read the marketing mantra and you’ll quickly understand that the essentials for business success are an unequivocal and distinct value proposition and a brand which evokes a portmanteau of neatly aligned qualities and characteristics. Moreover, you’ll need an elevator pitch that distils your value proposition into a few short sentences. Crack this, the handbook says, and you’re halfway to a listing on the Interbrand Top 100. It’s that easy. Or so we thought.

This strenuously asserted first principle of marketing – let’s call it business clarity for short – has long been understood to be a virtue as it provides customers with reassurance of what they are getting in exchange for their hard-earned money. However, with a more visible awareness of various market failures, not least the impact of visceral capitalism on the environment, certainty has become a less prized quality. We like the efficiencies of the capitalist system to deliver cheap, quality goods and services, but not at an unfettered cost to the planet.

Consistent with this sentiment is the rise of social purpose corporations that fuse profit ambition with fulfilment of ethical goals, such as TOMS, the footwear manufacturer that donates one pair of shoes to those without means for every pair purchased, along with the widespread adoption of corporate alliances with social causes.

Hit the re-set button

As the precepts of capitalism begin to be re-set – from ethical investment funds to environmentally-neutral supply chains – so too the reliance on marketing clarity demands a fresh look as companies are increasingly expected to perform a delicate hybrid role to meet the varying and oftentimes contradictory demands of its customers.

Companies encountering a conflict in competing principles have tended to utilise one of two strategies – either seeking to blend a range of competing beliefs into a single organisation, or, if the conflict is too broad to be reconciled within one unified entity, to create separate standalone businesses that espouse individual and unaligned principles.

Ambiguity as a plus?

However, recent research conducted by Saïd Business School in relation to the launch of Germany’s first Islamic bank has demonstrated how ambiguity – rather than clarity – has been instrumental in the company’s success.

The example of KT Bank’s apparent reconciliation of western banking principles and Islamic teaching has been achieved expressly through constructive ambiguity, offering different customer cohorts a different proposition and allowing all customers to feel enfranchised.

The research identified two ambiguity strategies. Polysemy or multiple meanings introduced vagueness into KT’s marketing communications. For instance, subtle religious iconography in marketing materials were interpreted as cultural artefacts by customers not versed in Islam, while those with knowledge of the faith would understand and invest in the religious connotations.

The second strategy was one of ‘many voices’ that enabled staff working for the bank to transit between commercial activity and religious devotion at prayer time within the bank’s physical space. These dual practices built organisational unity for staff and for the bank’s external custom, allowed clients themselves to define the nature of their engagement with the bank. This ambiguity enabled the company to be ‘elastic’ and respond to multiple demands internal and external without ‘breaking’.

It remains to be seen, however, when the first ‘ambiguous’ brand will find its way into the top 100.