Many companies have still not worked out how to compete in the digital age. Traditional companies bolt on digital offerings while new companies simply and optimistically describe themselves as ‘the Uber of …’ whatever sector they are in, before they are either bought up or fade away.

This is because most companies are still thinking in terms of products and value chains. Their strategies are based on the old idea that you add value to a product as it moves along the chain until it is delivered to the customer. Everyone in the chain has a single role – whether supplier, producer, distributor, or customer – and you win when your product delivers (or is perceived to deliver) more value to the customer than anyone else’s. What happens after the customer has bought the product is largely irrelevant.

The initial phase of digital disruption was interpreted as working along these lines: online bookshops provided a better service to customers than bricks-and-mortar stores with limited opening hours and stock; mp3 files allowed music-playing equipment to get smaller and lighter; digital cameras dispensed with expensive film and developing costs. Customers were delighted with these different products and the value chain was alive and well.

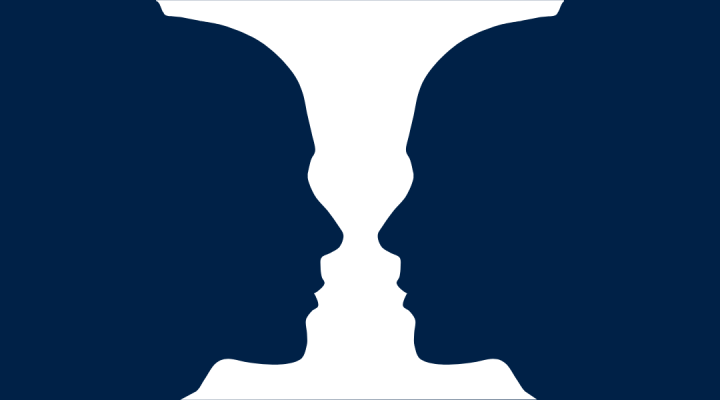

Or was it? In fact, in hindsight, even these initial product-focused disruptions were opening the door to what we see now as the ‘systemification’ of business, in which people, ideas, processes, and things relate to each other and create value together in complex business ‘ecosystems,’ not linear chains.

Customers, for example, are no longer passive recipients of the products and services, which store value produced by others. Instead, they actively participate in creating value. Some may have become hotel-owners (AirBNB) or taxi-drivers (Uber and Lyft). More are contributing to hotel and restaurant marketing (TripAdvisor reviews) or acting as journalists and photographers (almost all social media platforms) and reference editors (Wikipedia). They can be energy providers (solar panels), DJs (Spotify), film directors and music producers (YouTube).

At the same time, the idea of separate industrial sectors, in which similar companies compete in selling the same products and services, is well on its way out. Rather than buying dedicated music-playing devices, for example, most of us listen to music through our phones, and the best-selling phone manufacturer is in fact a computer company. And it’s only going to get more complicated, as fintech, proptech, edtech, and other portmanteau terms for new areas of activity suggest.

Companies that succeed in this new world will be those that stop focusing on adding value, but instead develop systems in which others can co-create value through their interactions. Take, for example, Rolls Royce’s innovative ‘power by the hour’ offering. Traditionally, an airline owning a plane—say a Boeing 707—would buy engines for its plane. Today, Rolls Royce offers a deal in which it retains the ownership of the engine, and the airline is only charged for the power it uses per hour flown. The airline no longer has to invest in financing and maintaining the engines. The traditional offering is a good (the engine) with a service (maintenance). The new offering is simply a service. Although the actors are the same, and the product is the same, there is a difference in the work sharing and risk sharing for each of the parties.

So the job of a strategist is no longer to do with adding, subtracting, or polishing links in the value chain. It is about reconfiguring the roles, actions, and interactions of the many actors in the company’s value creating system.

The focus is now not a standalone product or service, but an offering – a designed system of relationships and interactions that allow actors within the system to co-create value.

In developing an offering, strategists must consider people with different roles and skills who interact with each other; processes that enable these interactions; technology, which includes the hardware and software involved in the interactions; information, or the data involved; and work-sharing and risk-sharing formulae, or how the actors share the work and the risk.

These value-creating systems can also facilitate sustainability as goods, knowledge, and relationships remain within the system, rather than falling off the end of the value chain as soon as products are sold.

What’s not to like? Indeed, the surprise is that people persist in thinking in terms of value chains. But it’s not easy to change a large, established company. Many players, having witnessed the revolution in the music industry, for example, will realise that the co-creation of value can also mean a redistribution of the financial rewards associated with that value. That’s a consequence that can be hard to accept for people wedded to traditional models (and traditional levels of return).

The answer may be deliberately incremental change: introducing new offerings and value-creating systems by project teams that co-exist with traditional product-focused methods. Companies can experiment, doing more of what works and gradually abandoning what doesn’t. However slowly, value chains are on the way out.

Rafael Ramirez is the author (with Ulf Mannervik, Programme Director of the Oxford Networked Strategy Lab) of Strategy for a Networked World (2017, Imperial College Press).